Cells taken from the lungs of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have a larger accumulation of soot-like carbon deposits compared to cells taken from people who smoke but do not have COPD, according to a study led by University of Manchester researchers.

The study is published today (Wednesday) in ERJ Open Research [1]. Carbon can enter the lungs via cigarette smoke, diesel exhaust and polluted air.

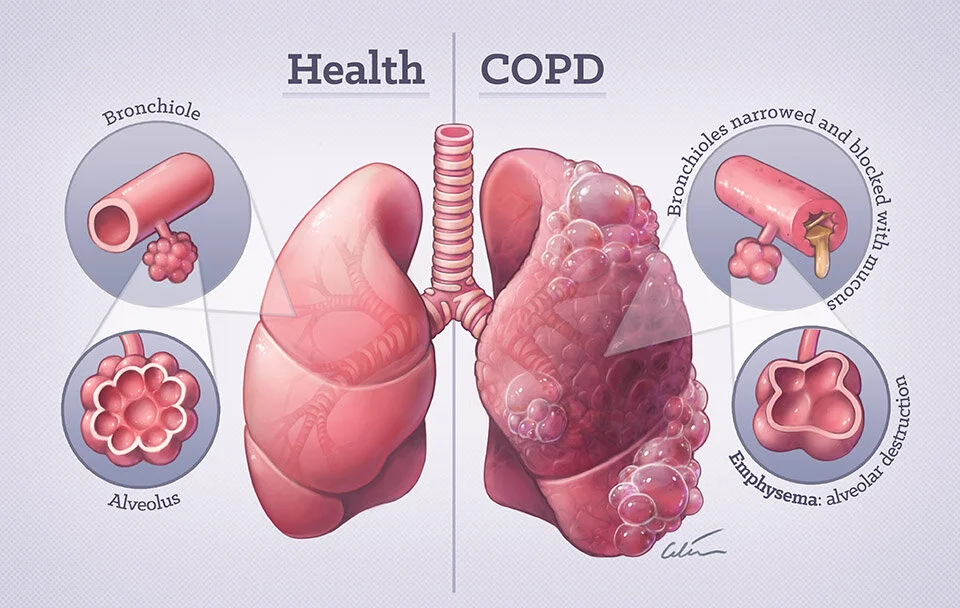

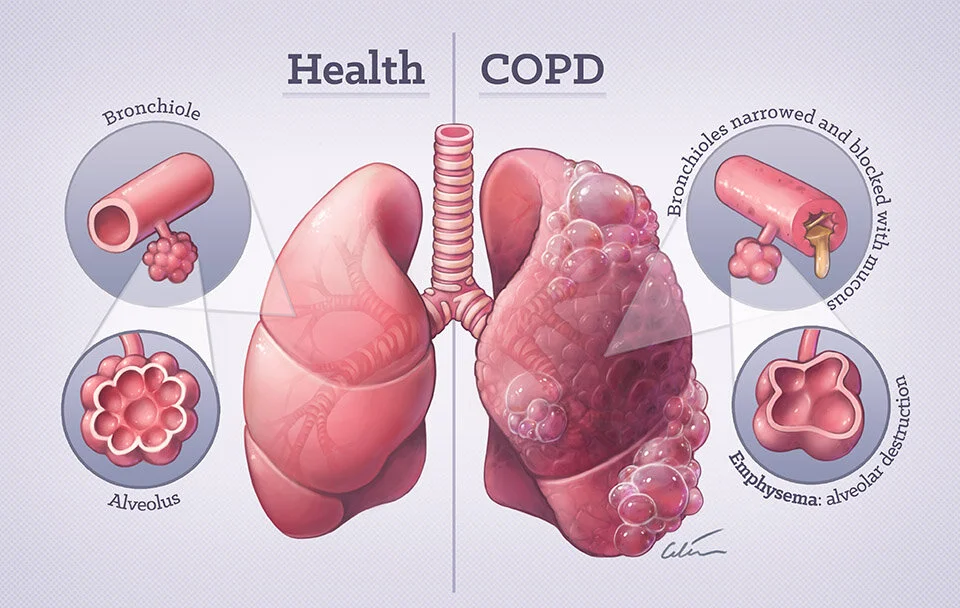

The cells, called alveolar macrophages, normally protect the body by engulfing any particles or bacteria that reach the lungs. But, in their new study, researchers found that when these cells are exposed to carbon they grow larger and encourage inflammation.

The research was led by Dr James Baker and Dr Simon Lea from The University of Manchester, UK, and funded by the North West Lung Centre Charity and the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Dr Baker, Research Associate within the NIHR Manchester BRC’s Respiratory Theme said: “COPD is a complex disease that has a number of environmental and genetic risk factors. One factor is exposure to carbon from smoking or breathing polluted air.

“We wanted to study what happens in the lungs of COPD patients when this carbon builds up in alveolar macrophage cells, as this may influence the cells’ ability to protect the lungs.”

The researchers used samples of lung tissue from surgery for suspected lung cancer. They studied samples (that did not contain any cancer cells) from 28 people who had COPD and 15 people who were smokers but did not have COPD.

Looking specifically at alveolar macrophage cells under a microscope, the researchers measured the sizes of the cells and the amount of carbon accumulated in the cells.

They found that the average amount of carbon was more than three times greater in alveolar macrophage cells from COPD patients compared to smokers. Cells containing carbon were consistently larger than cells with no visible carbon.

Patients with larger deposits of carbon in their alveolar macrophages had worse lung function, according to a measure called FEV1%, which quantifies how much and how forcefully patients can breathe out.

When the researchers exposed macrophages to carbon particles in the lab, they saw the cells become much larger and found that they were producing higher levels of proteins that lead to inflammation.